Can the Elephant and Dragon Tango?

Date: Oct 20, 2024

At the beginning of WWII, Churchill called the Soviet Union "a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma." Coming to the present, the same can be said for China. China gets a lot of coverage in the media regarding its expansionist actions, but little is known about its thinking.

Mao Tse Tung wanted to liberate the five fingers of Tibet: Arunachal (erstwhile NEFA), Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, and Bhutan. The issue flows from China's assertion of its sovereignty over Tibet and Aksai Chin being a natural extension of it. However, even historically, the Hans didn't consider Tibet as part of their territory. The only time Tibet was controlled by China was under the alien rule of the Mongols under the Yuan dynasty and the recent control by the Qing dynasty. This weakens China's claim over Tibetan territories, let alone the extent of Tibetan territories vis-a-vis Aksai Chin. If regal annexation forms the basis of a claim, India's Zorawar Singh Dogra reached the extents of Tibet.

India's MacMohan Line vs Macdonald McCartney Line

The elephant in the room for the Sino-Indian boundary dispute is the Simla Agreement of 1914, signed by British India and the Tibet Autonomous Region. India recognizes the boundary agreed upon under this agreement signed by Foreign Secretary MacMohan, after whom it is named. China denies any sovereign authority to Tibet and considers the agreement void. It conveniently considers another British proposal, the Macdonald McCartney line, as the basis for the boundary. The undemarcated boundary is a frequent source of conflict and clashes between the two Asian giants.

Rajiv Gandhi's 1988 visit to China marked a turning point in Sino-Indian relations, breaking decades of diplomatic freeze and laying the groundwork for future engagement. Building on this, P.V. Narasimha Rao signed the 1993 Peace and Tranquility Agreement, the first formal pact recognizing the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and committing both nations to peaceful border management.

To institutionalize dialogue, several mechanisms were established:

- 2003: Special Representative Mechanism – High-level diplomatic talks on boundary resolution.

- 2012: WMCC (Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination) – A platform for crisis management along the LAC.

- Senior Highest Military Commanders Meeting (SHMC) – A military-level dialogue to manage disengagement and stability.

These frameworks have helped prevent large-scale conflicts, though periodic border tensions continue to test their effectiveness.

October 2024 Disengagement

The October 2024 disengagement is the second step in the normalization of ties after the earlier de-escalation process. It was broadly guided by leaders at the highest levels, dubbed as the Kazan Consensus. The statements by ministries omit finer details of the patrolling agreement. However, some arrangement on patrolling has been reached.

A broader normalization of ties is underway with talks to resume Mansarovar Yatra, visas for businesses and journalists, and the resumption of flights. The tactical thaw in ties, earlier dubbed as "abnormal" by EAM SJ, should not be read as a strategic shift. Rather, it is pragmatism by both countries to hedge their chances against the upcoming Trump administration. India, by straitjacketing broader bilateral ties with the precondition of normalizing the boundary issue, has gained leverage against a slowing Chinese economy. The Hon'ble EAM, in a statement to Parliament, remarked:

"We remain committed to engaging with China through bilateral discussions to arrive at a fair, reasonable, and mutually acceptable framework for a boundary settlement."

Military Capabilities and Spending

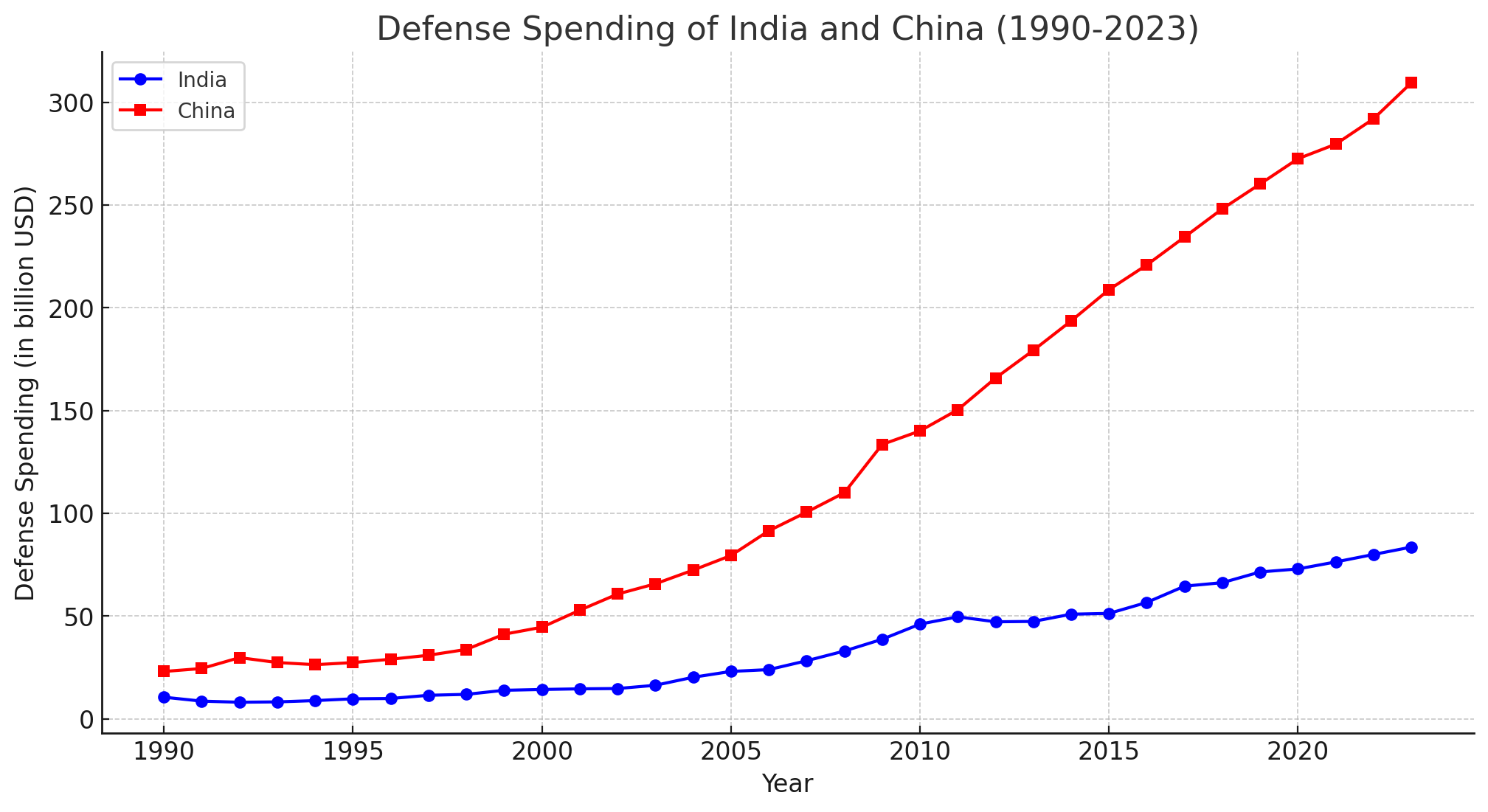

There exists an exponential gap between Indian and China's military spending and capabilities.

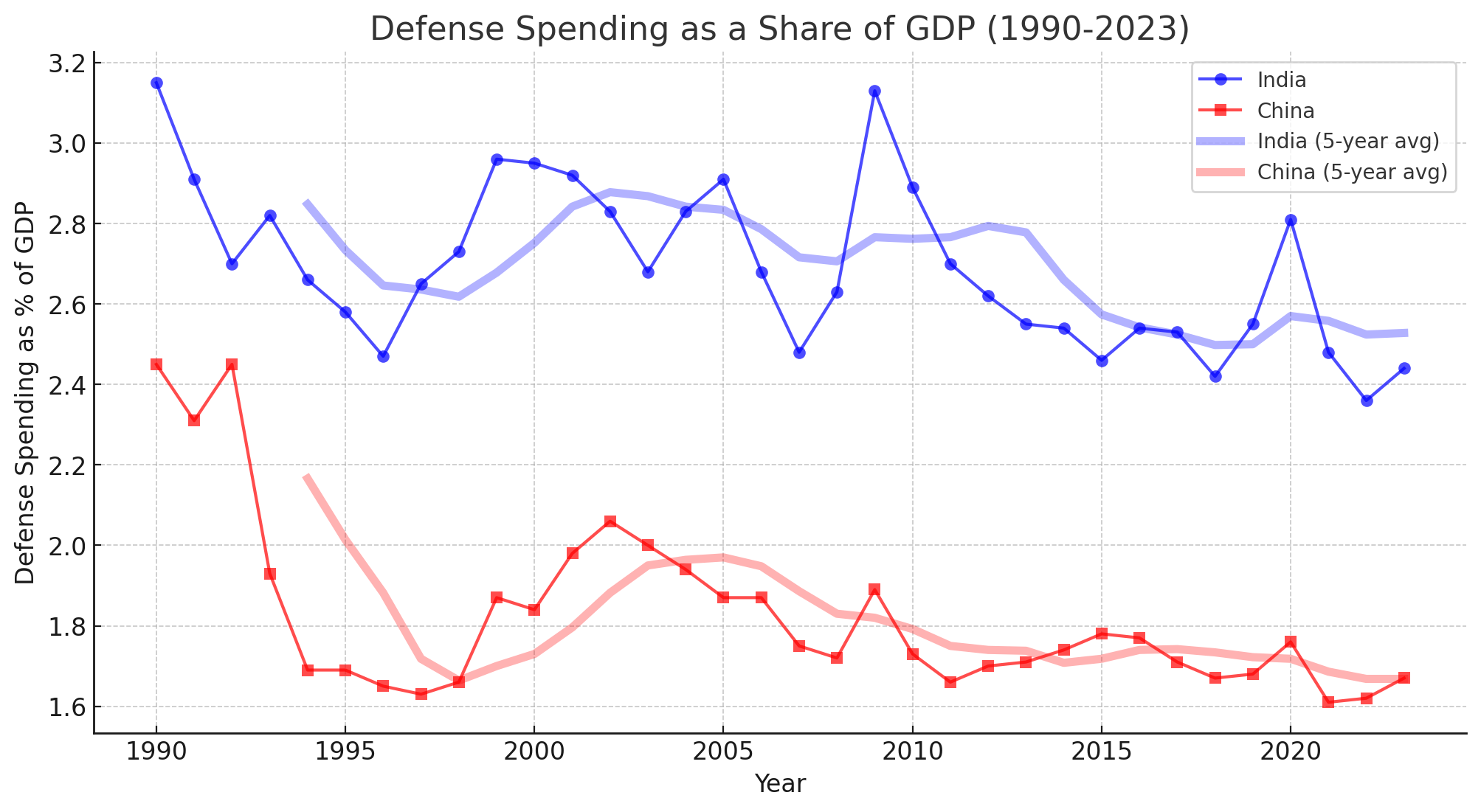

India's GDP was comparable with China's in 1990. However, it has to share a high burden of defence spending relative to its GDP. Whereas, China, leveraging its exponential GDP growth rate, has been able to keep its defence spending below 2% of GDP.

On the other hand, India's defence spending as a percentage of GDP has stabilized at 2.5%, which is at the lower end of the recommended spending by the Shekatkar Committee in 2015. India's defence needs require it to be at 3%.

With a defense gap of $160 Bn in FY24 ($231Bn - $71 Bn) in absolute terms, it leaves India in an extremely vulnerable position. Some estimates here have pegged China's true defence spending to be around $471 Bn. For context, US defence spending in 2024 is around $1.3 Tn.

Another key metric to look at is defence exports. India exported around $2.5 Bn in FY 2024 as compared to China's $3.24 Bn in FY22. More recent data for Chinese exports is not available, however, >60% of its exports go to Pakistan and >80% to Asia and Oceania.

De-induction on the LAC will ensure both the Asian giants can focus their resources on national development. It will also free up Indian resources to provide India an opportunity to become a maritime power, shedding its historic land myopia.

India's nuclear deterrence weakens against grey-zone warfare tactics of China, including Salami slicing of its territory. Hence, it becomes imperative to ensure that any such de-induction is verifiable, long-lasting, and comprehensive. India needs to bolster its satellite imagery capabilities to monitor any military activities in the dual-use Xiaokongs. It can leverage hyperspectral imaging for rich imagery with indigenous startups like PixxelSpace taking the lead. A possible détente, often termed as G2 with the US, reduces the scope for China to unburden the issue. Former Chinese Ambassador to India denied any scope for India needs to ensure military parity with China to force China's hand for a peaceful resolution of the dispute.

Update: Feb 2025

The possibility of emergence of Ecospheres of China in Asia, Russia in Europe, and the USA in the western hemisphere complicates conflict and coordination by great powers. Such spheres of influence will directly threaten the multipolar Asia vision of India. Recognition of Chinese hegemony in the region will be detrimental to the region's stability and the last nail in the coffin of the rules-based world order. The emerging great power politics presents new opportunities for India to shape a multipolar world.